Basics of Metadata: How It Helps Understand Your Data

Anuar Ustayev

Introduction

In the age of big data, raw datasets alone are seldom enough. Without context, understanding a table’s fields, provenance, or usage constraints can be a guessing game. Metadata—often described as “data about data”—fills this gap by providing structured, machine-readable descriptions of your datasets. In this article, we’ll explore:

- What metadata is, at a technical level

- Core metadata concepts including built-in information and external metadata.

- Basics of further ingestion of metadata in various systems.

Whether you’re building an internal data catalog or a public open-data portal, a robust metadata strategy is the key to making data discoverable, interoperable, and reusable.

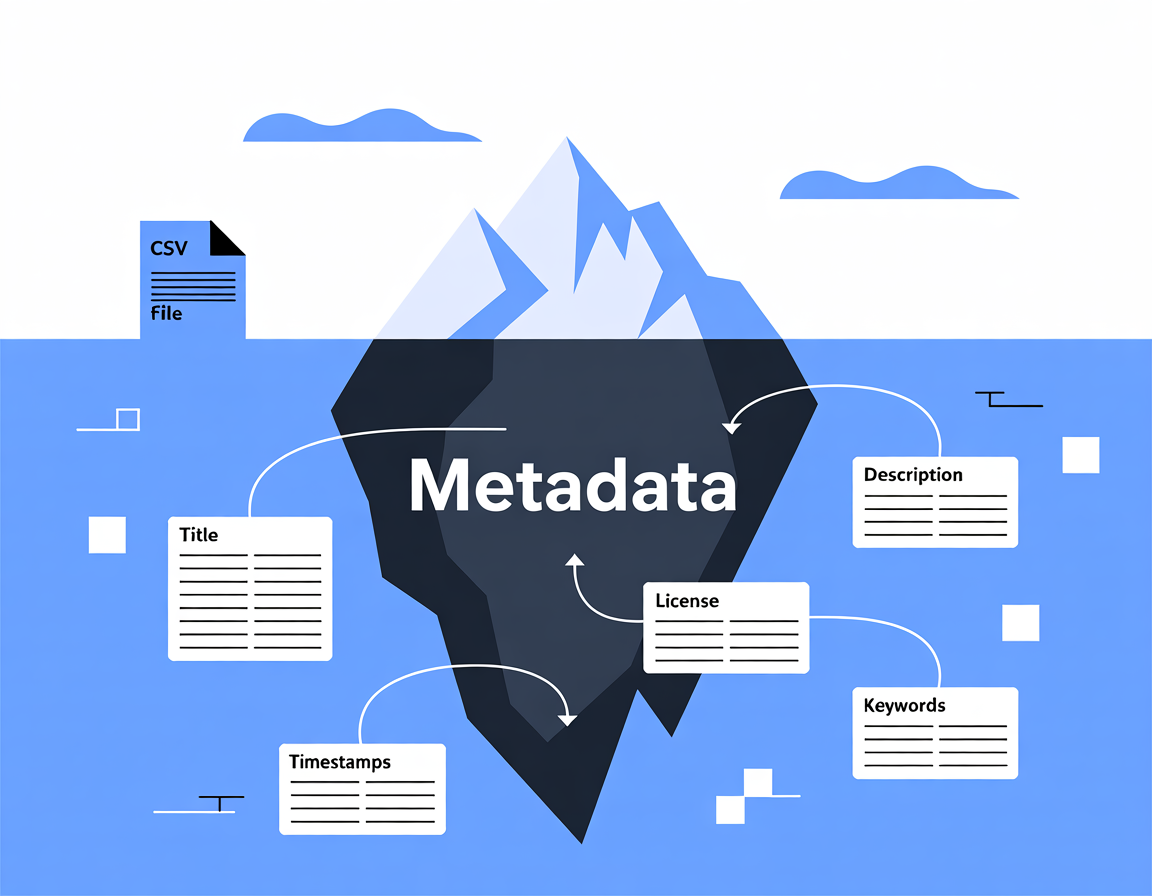

1. Defining Metadata

Metadata is information that describes the characteristics and context of a data asset. It bridges the gap between raw data and meaningful insight by answering questions such as:

- What the data represents (descriptive metadata)

- How it is structured or formatted (structural metadata)

- Who, when, and where the data was created or modified (administrative metadata)

At the simplest level, metadata can be built into your storage layer (e.g., file name, format, timestamps). For richer context, you can supply external metadata files (JSON, YAML, XML, or simple text) that complement and enhance built-in attributes.

2. From Built-In to External Metadata: A Step-by-Step Example

Let’s say you have a simple CSV file of temperature readings:

// File on disk:

temperature-readings-20250528.csv

// Content preview:

timestamp,value

2025-05-28T00:00:00Z,15.2

2025-05-28T01:00:00Z,14.9

...

2.1. Built-In Metadata

Every file system (and HTTP response) carries minimal metadata. For our CSV:

- File name:

temperature-readings-20250528.csv - Media type:

text/csv

These two attributes already tell machines:

- what the file is called, and

- how to parse it (as comma-separated values).

But to your users—or to a search engine—you need richer context.

Note about other built-in metadata:

Beyond file name and media type, file systems and delivery protocols expose several other built-in metadata attributes you can leverage before you even add an external metadata file:

- File System Attributes

- Size (

Content-Lengthin HTTP): the total byte length of the CSV.- Timestamps:

- Created (

birthtimeon many Unix-style systems)- Last modified (

mtime)- Last accessed (

atime)- Permissions & Ownership: who owns the file and its read/write/execute bits.

- HTTP/Transport Metadata (when serving over HTTP)

- ETag or Last-Modified header: for cache validation.

- Content-Encoding: if you gzip/brotli the CSV in transit.

- Content-Disposition: suggests a download filename or whether to display inline.

- CSV-Specific “Built-In” Info (derivable by quickly inspecting the file)

- Header Row: column names—essential structural metadata.

- Row Count: number of records (you can compute this cheaply on ingest).

- Character Encoding: e.g. UTF-8 vs. ISO-8859-1 (often exposed as

charsetin the MIME type).

2.2. External Metadata

Often, file names and media types alone are insufficient to convey the context users need. To enrich your CSV with human-readable information, you can provide an external metadata file. For a single attribute—such as a title—you might start with a basic text file named metadata.txt:

Hourly temperature readings for May 28, 2025

While this simple file supplies a clear title, real-world use cases typically require multiple metadata fields (e.g., title, description, type). To represent these as structured data that programs can parse reliably, a key-value format is ideal. Consider the following YAML example:

title: Hourly temperature readings for May 28, 2025

description: |

This CSV contains one-hour-interval temperature measurements

recorded in Almaty, Kazakhstan on May 28, 2025. All timestamps

are in UTC. Data sourced from XXX weather station.

What is YAML?

YAML ("YAML Ain't Markup Language") is a human-friendly serialization format. Its indentation-based syntax and key-value structure make it easy to author and parse, making YAML a popular choice for metadata, configuration, and data interchange.

The same information rendered in tabular form:

| Metadata Field | Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

title | Hourly temperature readings for May 28, 2025 | Provides a concise, human-readable name—easier for users to scan than a raw filename |

description | This CSV contains one-hour-interval temperature measurements recorded in Almaty, Kazakhstan on May 28, 2025. All timestamps are in UTC. Data sourced from XXX weather station. | Offers detailed context upfront, improving relevance judgment without inspecting data |

Why add external metadata?

Providing even a simple companion metadata file gives users immediate context—transforming opaque filenames into understandable resource descriptions. It enhances discoverability, improves usability, and lays the groundwork for rich search and filtering features.

2.3. Taking It Further: Additional Attributes

Once you’ve mastered title and description, you can add:

- keywords: e.g.

temperature, Almaty, time series - license: e.g.

CC-BY-4.0 - provenance: who collected it and when (e.g.

collectedBy: XXX weather station).

Each new attribute is just another line in your metadata file:

keywords: temperature,Almaty,time series

license: CC-BY-4.0

collectedBy: XXX weather station

Many systems would automatically pick these up—no custom code required.

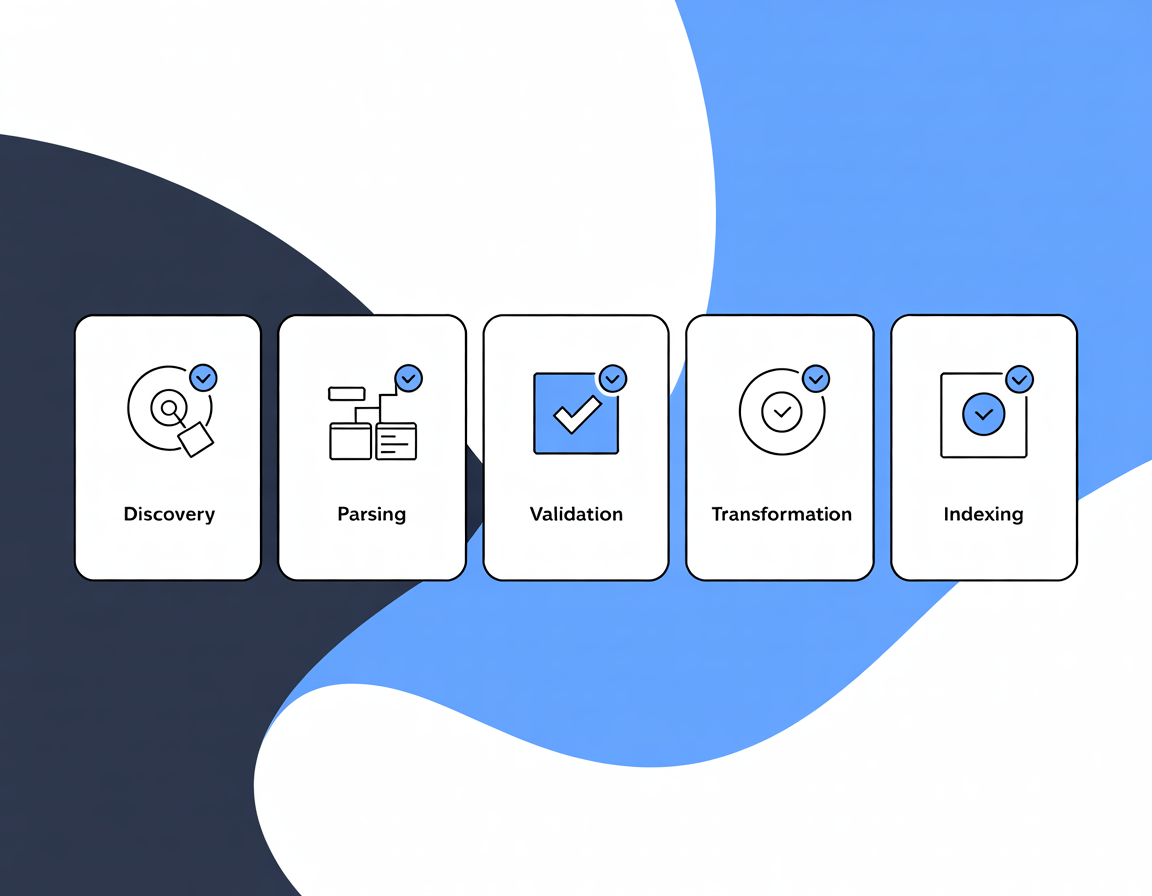

2.4. How Ingestion Works

- Discovery

- An ingestion pipeline identifies data files and their companion metadata files (e.g.,

.meta.txt,.json, or.yaml).

- An ingestion pipeline identifies data files and their companion metadata files (e.g.,

- Parsing

- Read built-in metadata attributes (filename, media type, file size, timestamps) directly from the file system or HTTP headers.

- Parse the external metadata into structured fields (e.g.,

title,description,keywords).

- Validation

- Validate parsed metadata against a predefined schema or set of rules to ensure completeness and correctness.

- Transformation

- Normalize and transform metadata values (e.g., convert date formats, split comma lists into arrays).

- Indexing

- Store both built-in and external metadata in a search or catalog index, mapping specific fields to facets, full-text search, and structured exports (JSON‑LD, DCAT).

- This index powers discovery features like faceted filters, semantic ranking, and metadata exports.

2.5. Why This Matters

- Clarity for Users: A friendly title beats a cryptic filename.

- Better Search: Rich text in

descriptionfuels full-text relevancy ranking. - Faceted Filters: Adding

keywordsandlicenseturns those into clickable filters. - Automation: Keep your metadata alongside your data; pipelines stay simple.

By starting with two built-in attributes and a tiny external text file, you can already transform raw CSV dumps into a fully searchable, self-documenting dataset. From here, extending to full JSON-LD or DCAT becomes a natural next step.

Conclusion

Implementing metadata is not just a best practice—it's essential for unlocking the value of your data. By combining built-in attributes (file name, media type, timestamps) with external metadata files, you provide the context users need to discover, understand, and trust your datasets. A clear metadata strategy powers faceted search, semantic ranking, and linked-data features that scale from a simple CSV repository to enterprise-grade data catalogs. Start small with human-readable titles and descriptions, then grow your metadata alongside your data products to build truly data-driven experiences.